Coming soon: Angelo Ippolito and the history of

Introduction

1947 -51

Early Abstractions

1952 -63

Action and Atmosphere

1961

The Berkeley Series

1962 -74

Shaped Space

1963 -67

Watercolors

1964 -69

Midwestern Abstractions

1969 -70

Horizons and Hard Edges

1970 -75

The Intimate Landscape

1976 -98

Comic Relief

1976 -85

The Upstate Landscapes

1984 -89

The Regatta Series

1988 -93

Aegean Atmospheres

1993 -2001

Action and Impulse

Introduction

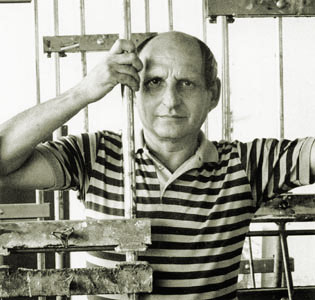

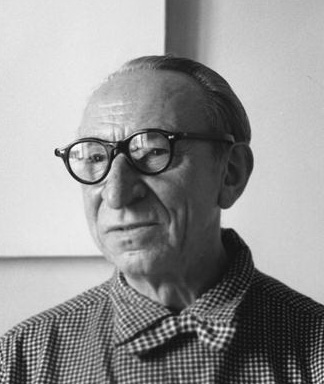

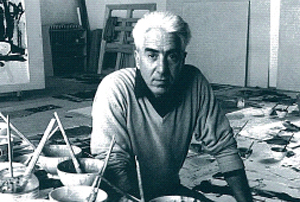

Welcome to the official site for the art and life of Angelo Ippolito, internationally exhibited painter, renowned member of the New York School of abstract expressionism, and beloved teacher.

Welcome to the official site for the art and life of Angelo Ippolito, internationally exhibited painter, renowned member of the New York School of abstract expressionism, and beloved teacher.

Ippolito (1922-2001) produced a body of oils on canvas, works on paper, and assemblages renowned for their lyrical color, light, and compositional rigor. An emigré from Italy at age nine, he helped usher in the downtown New York arts scene by co-founding the influential Tanager gallery in 1952, earning him the moniker "Mr. Tenth Street." His paintings gained acclaim for their "brilliant color" (Fairfield Porter) and "joyous lyricism" (Dore Ashton), and are featured in numerous public collections including New York's MoMA, Whitney, and Metropolitan museums.

This chronology highlights the evolution of Ippolito's oils on canvas, touching briefly on paper and sculptural works but ignoring a number of separate creative practices such as photography. As art historian Kenneth Lindsay writes in Ippolito's 1975 retrospective catalogue, "he plays out his life like a good jazz musician who 'feels' the right point of entry and improvises a chorus within acknowledged limits of form....the 'beat' of his change of environment also describes the way he paints." If there is regularity to Ippolito's aesthetic beat, it is to be found in his alternation between periods of experimentation (with hard-edged painting, still lives, or regatta motifs) and periods of integration (as in his "color as light" and Aegean paintings).

This chronology highlights the evolution of Ippolito's oils on canvas, touching briefly on paper and sculptural works but ignoring a number of separate creative practices such as photography. As art historian Kenneth Lindsay writes in Ippolito's 1975 retrospective catalogue, "he plays out his life like a good jazz musician who 'feels' the right point of entry and improvises a chorus within acknowledged limits of form....the 'beat' of his change of environment also describes the way he paints." If there is regularity to Ippolito's aesthetic beat, it is to be found in his alternation between periods of experimentation (with hard-edged painting, still lives, or regatta motifs) and periods of integration (as in his "color as light" and Aegean paintings).

The series descriptions are from Irving Sandler, Angelo Ippolito (Binghamton, NY: Binghamton University, 2004). Italics in a series title indicate that the artist chose it himself. All artworks pictured belong to the Estate of Angelo Ippolito unless otherwise indicated.

1947-51

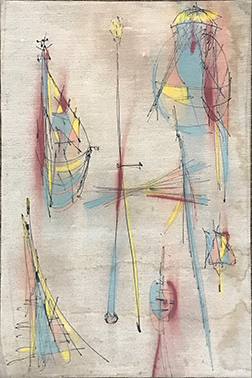

Early Abstractions: The Cubist Impulse

Like many artists of his generation, Ippolito went to school on the GI Bill after his return from duty in the south Pacific in 1945.

Like many artists of his generation, Ippolito went to school on the GI Bill after his return from duty in the south Pacific in 1945.

Although he had never graduated from high school, he skirted formal secondary education altogether, studying art instead with painters Amedee Ozenfant and John Ferran in New York from 1946 to 1948 and with Afro in Rome in 1950.

Ippolito's earliest paintings reflect the Cubist influence of his teachers. Although his brushwork loosened in subsequent decades, Ippolito's commitment to a strong pictorial structure suggests that Cubism provided a sound foundation for his compositions even if its fractured geometries rarely resurfaced amidst his increasingly atmospheric brushwork.

Ippolito's earliest paintings reflect the Cubist influence of his teachers. Although his brushwork loosened in subsequent decades, Ippolito's commitment to a strong pictorial structure suggests that Cubism provided a sound foundation for his compositions even if its fractured geometries rarely resurfaced amidst his increasingly atmospheric brushwork.

1952-63

Action and Atmosphere: The Tanager Days

In 1951 Ippolito returned to New York from his travels in Europe in time to catch the now-famous 9th Street show highlighting the works of first-generation New York School artists such as Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. While living on 10th Street, Ippolito frequented the same neighborhood haunts as older Abstract Expressionists, notably the Artist's Club and Cedar Tavern.

In 1951 Ippolito returned to New York from his travels in Europe in time to catch the now-famous 9th Street show highlighting the works of first-generation New York School artists such as Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline. While living on 10th Street, Ippolito frequented the same neighborhood haunts as older Abstract Expressionists, notably the Artist's Club and Cedar Tavern.

In 1952, however, Ippolito and four of his peers established the first of the downtown cooperative galleries, the Tanager, in a move to offer an artist-centered alternative to the commercial galleries that beckoned from 57th street. It was at the Tanager that Ippolito first exhibited a luminous series of canvases inspired by the landscape of his birthplace in southern Italy.

Calling Ippolito's inaugural exhibition at the midtown Bertha Schaeffer Gallery "a notable event," critic Robert Rosenblum wrote that "his canvases present abstract analogies to a landscape vision, suggesting earth, horizon line and sky; yet the separate realms of land and air are most often fused together in a single coloristic unity of closely-valued hues." Over the following decade, the fusion of earth and sky in Ippolito's canvases progressed to the point where the horizon vaporized, leaving only atmosphere.

Calling Ippolito's inaugural exhibition at the midtown Bertha Schaeffer Gallery "a notable event," critic Robert Rosenblum wrote that "his canvases present abstract analogies to a landscape vision, suggesting earth, horizon line and sky; yet the separate realms of land and air are most often fused together in a single coloristic unity of closely-valued hues." Over the following decade, the fusion of earth and sky in Ippolito's canvases progressed to the point where the horizon vaporized, leaving only atmosphere.

Having relinquished the solid forms of Cubism and the landscape, Ippolito was left with color alone to anchor his airy compositions. Reviewing a later exhibition at Bertha Schaeffer, fellow painter and critic Fairfield Porter wrote, "Ippolito is one of a few Non-Objective artists who uses brilliant color as his material instead of something to dress the painting up with."

Having relinquished the solid forms of Cubism and the landscape, Ippolito was left with color alone to anchor his airy compositions. Reviewing a later exhibition at Bertha Schaeffer, fellow painter and critic Fairfield Porter wrote, "Ippolito is one of a few Non-Objective artists who uses brilliant color as his material instead of something to dress the painting up with."

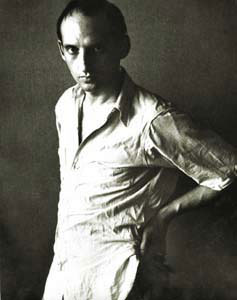

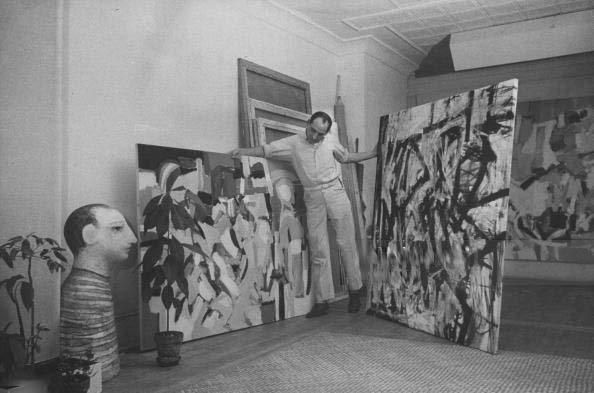

Photo of Angelo Ippolito in his 10th Street studio by James Burke.

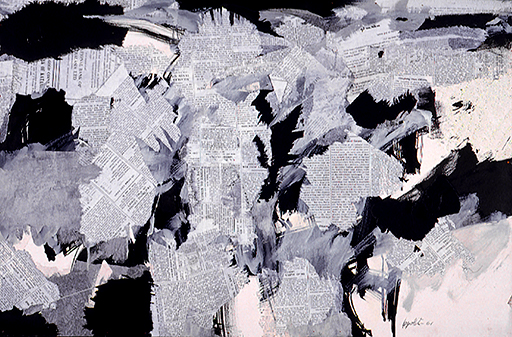

1961

Black and White As Color: The Berkeley Series

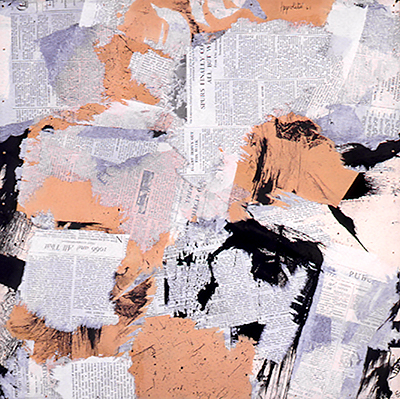

In 1961 Ippolito moved to the University of California at Berkeley for three semesters as a visiting artist. The change of landscape immediately had an impact on his work; this artist who critic Hilton Kramer described as a colorist "first and last" was too awestruck by the intense light of the Californian sun to paint in color. Ippolito's response was a series of black-and-white collages and drawings in ink, oil, and newsprint.

In 1961 Ippolito moved to the University of California at Berkeley for three semesters as a visiting artist. The change of landscape immediately had an impact on his work; this artist who critic Hilton Kramer described as a colorist "first and last" was too awestruck by the intense light of the Californian sun to paint in color. Ippolito's response was a series of black-and-white collages and drawings in ink, oil, and newsprint.

Despite their austere palette and contrasting tones, the Berkeley works retain the spacious composition and light touch that attracted acclaim to his large-scale New York canvases. Color in the Berkeley works, however, derives from subtle shades of ink and nuances of newsprint tint rather than primary colors squeezed from a tube.

Despite their austere palette and contrasting tones, the Berkeley works retain the spacious composition and light touch that attracted acclaim to his large-scale New York canvases. Color in the Berkeley works, however, derives from subtle shades of ink and nuances of newsprint tint rather than primary colors squeezed from a tube.

1962-74

Shaped Space

Ippolito's approach to pictorial space underwent another shift when he visited the Midwest in the mid-to-late 1960s. In 1962 he hinged two vertical panels to create Corner Landscape, an intimate expanse of light and color. Two years later he began sewing circular or oval insets into a series of small oils on canvas. While Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo had experimented with circular paintings, in Ippolito's hands the tondo produces a new kind of spatial disjunction, suggesting a lens that reveals a close-up vision of a distant landscape.

Ippolito's approach to pictorial space underwent another shift when he visited the Midwest in the mid-to-late 1960s. In 1962 he hinged two vertical panels to create Corner Landscape, an intimate expanse of light and color. Two years later he began sewing circular or oval insets into a series of small oils on canvas. While Renaissance artists such as Michelangelo had experimented with circular paintings, in Ippolito's hands the tondo produces a new kind of spatial disjunction, suggesting a lens that reveals a close-up vision of a distant landscape.

Ippolito's experiments with the sculptural possibilities of shaped canvases reached its climax a decade later, with a five-foot tall cubic painting exhibited in his 1975 retrospective at Binghamton University. The unusual form of this work re-creates the boundless Midwestern horizon, albeit in an inverted form where the viewer is outside rather than inside the landscape.

Ippolito's experiments with the sculptural possibilities of shaped canvases reached its climax a decade later, with a five-foot tall cubic painting exhibited in his 1975 retrospective at Binghamton University. The unusual form of this work re-creates the boundless Midwestern horizon, albeit in an inverted form where the viewer is outside rather than inside the landscape.

1963-67

Watercolor and the Return to Landscape

A series of small watercolors painted mostly in Michigan represent Ippolito's most literal return to the landscape. Although grounded in representational subject matter, these delicate images nonetheless remain airy and weightless. Ippolito's watercolors evoke the quote by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche that reviewer Alfred Frankenstein applied to Angelo's oils from the same decade: "What is good is easy; everything divine runs on light feet."

A series of small watercolors painted mostly in Michigan represent Ippolito's most literal return to the landscape. Although grounded in representational subject matter, these delicate images nonetheless remain airy and weightless. Ippolito's watercolors evoke the quote by philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche that reviewer Alfred Frankenstein applied to Angelo's oils from the same decade: "What is good is easy; everything divine runs on light feet."

1964-69

Form and Farmland: Midwestern Abstractions

In the latter 1960s Ippolito earned tenure at Michigan State University, where once again his work fell under the sway of the local landscape. As always, the artist translated his geographic inspirations into his own formal vocabulary: country roads sharpened into diagonal stripes; grain silos melted into brushy verticals; wheat fields blurred into trapezoids of ochre and amber.

In the latter 1960s Ippolito earned tenure at Michigan State University, where once again his work fell under the sway of the local landscape. As always, the artist translated his geographic inspirations into his own formal vocabulary: country roads sharpened into diagonal stripes; grain silos melted into brushy verticals; wheat fields blurred into trapezoids of ochre and amber.

Like the agrarian communities surrounding him, Ippolito's Midwestern compositions edged organic growth within geometric borders.

Like the agrarian communities surrounding him, Ippolito's Midwestern compositions edged organic growth within geometric borders.

His attempt to distill the visual patterns of America's farmlands down to its pictorial essence was not lost on city-bound critics; of Nude Landscape and Paulding, Hilton Kramer wrote in The New York Times, "there is a vivid feeling for place as well as for the exigencies of design."

1969-70

Horizons and Hard Edges

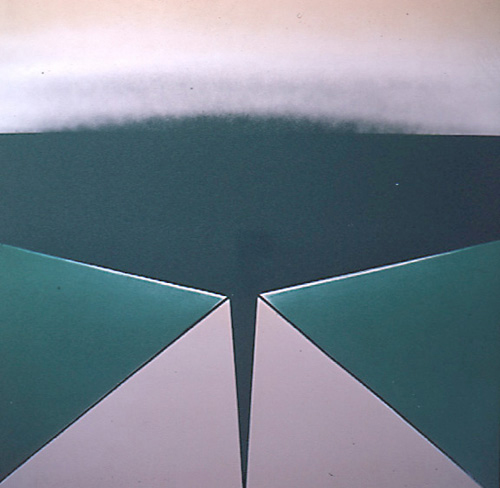

During his early years in the Midwest, even the most structured of Ippolito's canvases were animated by unruly brushstrokes bursting forth here and there amidst the hard edges. Toward the end of Ippolito's sojourn in the Michigan, however, geometry temporarily gained the upper hand and squeezed gesture out of the frame altogether. In these canvases from the end of the decade, brushy trees and amorphous fields have conceded the canvas to sharp-angled buildings and impossibly tidy yards.

During his early years in the Midwest, even the most structured of Ippolito's canvases were animated by unruly brushstrokes bursting forth here and there amidst the hard edges. Toward the end of Ippolito's sojourn in the Michigan, however, geometry temporarily gained the upper hand and squeezed gesture out of the frame altogether. In these canvases from the end of the decade, brushy trees and amorphous fields have conceded the canvas to sharp-angled buildings and impossibly tidy yards.

For a stark evocation of the human subjugation of nature, Ippolito turned to Detroit for medium and imagery. Earlier painters David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jackson Pollock had turned to automobile lacquer for its quick drying time, but Ippolito was more interested in its metallic color and sheen. His imagery for these lacquered works, fittingly enough, was the open road; this artist who had assiduously avoided painting a straight horizon line into his abstracted landscapes now brought that horizon directly to his viewer's feet, at times daring them to peek over its edge.

For a stark evocation of the human subjugation of nature, Ippolito turned to Detroit for medium and imagery. Earlier painters David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Jackson Pollock had turned to automobile lacquer for its quick drying time, but Ippolito was more interested in its metallic color and sheen. His imagery for these lacquered works, fittingly enough, was the open road; this artist who had assiduously avoided painting a straight horizon line into his abstracted landscapes now brought that horizon directly to his viewer's feet, at times daring them to peek over its edge.

1970-75

The Intimate Landscape

In 1971 Ippolito moved to a farmhouse on a hillside near Vestal, New York, to take a teaching position in the Binghamton University art department. As soon as he relinquished the Midwestern plains for Vestal's mountainous terrain, geometry loosened its tight grip on his brushwork and compositions--as though in returning to a landscape reminiscent of his birthplace amidst the Apennines Ippolito was exchanging the precise severity of the Midwest for an informal Mediterranean baroque.

In 1971 Ippolito moved to a farmhouse on a hillside near Vestal, New York, to take a teaching position in the Binghamton University art department. As soon as he relinquished the Midwestern plains for Vestal's mountainous terrain, geometry loosened its tight grip on his brushwork and compositions--as though in returning to a landscape reminiscent of his birthplace amidst the Apennines Ippolito was exchanging the precise severity of the Midwest for an informal Mediterranean baroque.

Although Ippolito often doubled back on himself during the course of his geographic and stylistic peregrinations, Ippolito always uncovered something new even in familiar territory. As his paintings from the 1950s built on an invisible scaffold inherited from his Cubist drawings of the 1940s, so in his return to a painterly style in 1970 Ippolito brought along a dash of the geometric precision of his hard-edged works from the 1960s.

This geometric armature made possible spaces of great complexity, in which still life motifs such as vases and tables share the picture plane with landscape elements such as fields and trees. If his tondi from the early 1960s signaled abrupt changes of scale or perspective with a literal hole in the canvas, now such changes blended seamlessly into a common vista.

This geometric armature made possible spaces of great complexity, in which still life motifs such as vases and tables share the picture plane with landscape elements such as fields and trees. If his tondi from the early 1960s signaled abrupt changes of scale or perspective with a literal hole in the canvas, now such changes blended seamlessly into a common vista.

As always, Ippolito's primary instrument for unifying disparate spaces into a single pictorial setting was color--not the facile conciliation of a politely restrained palette, but daring passages of cobalt blue, acidic yellow, and vermilion. As Hilton Kramer wrote of Ippolito's still-life inspired abstractions, "the pleasure of color remains his primary concern, and he is a virtuoso in the handling of it. Some of his finest effects, in these new paintings, are achieved when he is juggling bold areas of hot color with an almost reckless abandon."

1976-98

Comic Relief: American Collages and Tableaux Metaphysiques

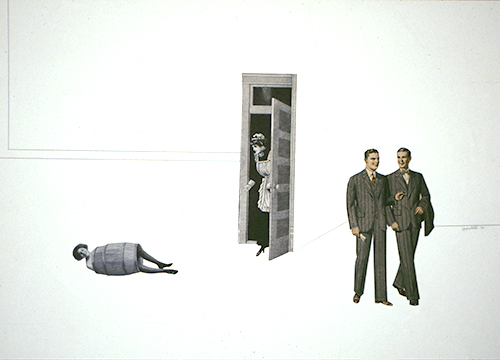

Ippolito's eye for striking juxtapositions wasn't confined to choices of color for his oil paintings. An avid collector of flea-market figurines, magazines, and other knickknacks, Ippolito started in 1976 to mine his unusual collections as artistic material for a whimsical series of collages and assemblages.

Ippolito's eye for striking juxtapositions wasn't confined to choices of color for his oil paintings. An avid collector of flea-market figurines, magazines, and other knickknacks, Ippolito started in 1976 to mine his unusual collections as artistic material for a whimsical series of collages and assemblages.

To create his American Collages, exhibited during the United States' bicentennial year, Ippolito snipped vintage illustrations of bowler hats, children's suits, sailing ships, corsets, and long underwear ads from turn-of-the-century editions of the Saturday Evening Post and Popular Mechanics. Plucked from their original context, these castaway cultural icons seem to meet by chance on Ippolito's minimal white stage in what Hilton Kramer called "a vastly amusing carnival of dreams."

To create his American Collages, exhibited during the United States' bicentennial year, Ippolito snipped vintage illustrations of bowler hats, children's suits, sailing ships, corsets, and long underwear ads from turn-of-the-century editions of the Saturday Evening Post and Popular Mechanics. Plucked from their original context, these castaway cultural icons seem to meet by chance on Ippolito's minimal white stage in what Hilton Kramer called "a vastly amusing carnival of dreams."

A year later Ippolito began a three-dimensional series called Tableaux Metaphysiques, in which he juxtaposed quirky figurines from wedding cakes or bowling trophies in unlikely settings. The artist described these constructions as a way to "rescue" these creatures of kitsch--be they toy cows or saltshakers--from their throwaway fate. Both the American Collages and Tableaux Metaphysiques expose the play at the center of Ippolito's artistic process--play that may be less evident in, but is just as crucial to, the artist's painterly compositions.

1976-85

Color As Light: The Upstate Landscapes

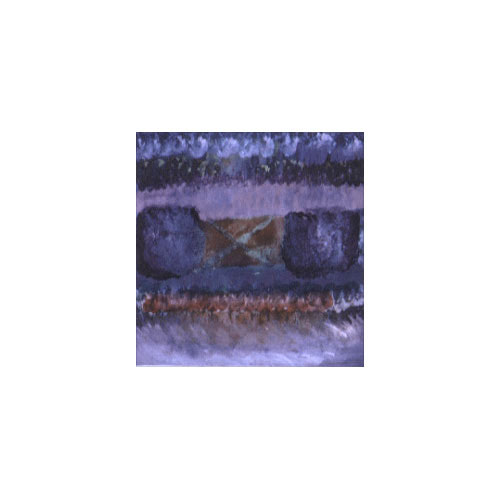

Around 1976, Ippolito's color broke free of its role in describing form and assumed center stage, spilling across the canvas into luminous clouds or shards of yellow-orange and blue-violet hues.

Around 1976, Ippolito's color broke free of its role in describing form and assumed center stage, spilling across the canvas into luminous clouds or shards of yellow-orange and blue-violet hues.

If there is a genre to these chromatic fantasies, it is probably landscape--but it is the vertical landscape of the Appalachians rather than the horizontal landscape of the plains. At times this vertical composition recalls the cruciform structure implicit in Ippolito's works from the 1950s. Yet in these mature abstractions the palette is more precise, as though Ippolito's discursion into representation in the intervening years recalibrated his "color pitch." The effect is gentler than the agitated canvases of the 1950s; although high-keyed yellows and oranges pervade this series, a more subtle radiance derives from a compositional strategy in which a given color vibrates in contrast with its neighboring colors but in sync with similar patches of color in other areas of the canvas.

If there is a genre to these chromatic fantasies, it is probably landscape--but it is the vertical landscape of the Appalachians rather than the horizontal landscape of the plains. At times this vertical composition recalls the cruciform structure implicit in Ippolito's works from the 1950s. Yet in these mature abstractions the palette is more precise, as though Ippolito's discursion into representation in the intervening years recalibrated his "color pitch." The effect is gentler than the agitated canvases of the 1950s; although high-keyed yellows and oranges pervade this series, a more subtle radiance derives from a compositional strategy in which a given color vibrates in contrast with its neighboring colors but in sync with similar patches of color in other areas of the canvas.

The form emerges from this game of contrasting and matching colors. As the artist told Kenneth Lindsay in 1974, "When I find the color of the painting I find the form....[color] gives me a time and a place."

1984-89

The Regatta Series

If the "color as light" abstractions of the late 1970s and early 1980s were informed by the artist's prior excursions into landscape imagery, his Regatta series represents another intrepid cruise into uncharted pictorial waters. In the early 1980s Ippolito's planes of color began to stand out from an increasingly monochromatic picture plane. From 1984 to 1985 these planes took on recognizable, if abstracted shapes: pennants, sails, and other nautical motifs emerged in Ippolito's abstractions, as though the very canvas he painted on were re-asserting its material heritage as sailing cloth.

If the "color as light" abstractions of the late 1970s and early 1980s were informed by the artist's prior excursions into landscape imagery, his Regatta series represents another intrepid cruise into uncharted pictorial waters. In the early 1980s Ippolito's planes of color began to stand out from an increasingly monochromatic picture plane. From 1984 to 1985 these planes took on recognizable, if abstracted shapes: pennants, sails, and other nautical motifs emerged in Ippolito's abstractions, as though the very canvas he painted on were re-asserting its material heritage as sailing cloth.

These paintings continue a trend inaugurated by the "color as light" paintings away from pictorial foci clustered near the center of the canvas. The middle of most Regatta paintings is vacant, with most of the action taking place at the edges of the frame or at seemingly random intersections of color planes. Compositions that seem to read as a quick gestalt turn out upon closer inspection to produce strong spatial ambiguities. Paintings such as Mare Verde or Regatta no. 7 leave unresolved the question of which planes advance or recede, just as Sails leaves open the question of which blue patch is sky and which is ocean.

These paintings continue a trend inaugurated by the "color as light" paintings away from pictorial foci clustered near the center of the canvas. The middle of most Regatta paintings is vacant, with most of the action taking place at the edges of the frame or at seemingly random intersections of color planes. Compositions that seem to read as a quick gestalt turn out upon closer inspection to produce strong spatial ambiguities. Paintings such as Mare Verde or Regatta no. 7 leave unresolved the question of which planes advance or recede, just as Sails leaves open the question of which blue patch is sky and which is ocean.

The odd angles and juxtapositions of the Regatta paintings suggest a photograph that is cropped so perversely that its viewer cannot tell what perspective the shot is taken from or even what exactly is depicted. And yet the setting for these enigmatic canvases is unquestionably the sea; as is his wont, Ippolito has evoked a sense of place without resorting to an illustrative depiction.

1988-93

Aegean Atmospheres

In 1988 Ippolito spent the first of a series of summers teaching and making art in the Mediterranean. In the first summer he found himself on the Greek island of Samos without his usual complement of canvases and paints, so he turned to small-scale works on paper to express the limpid air and light of the Aegean Sea outside his window.

In 1988 Ippolito spent the first of a series of summers teaching and making art in the Mediterranean. In the first summer he found himself on the Greek island of Samos without his usual complement of canvases and paints, so he turned to small-scale works on paper to express the limpid air and light of the Aegean Sea outside his window.

Although he had brought along an expensive set of the finest Windsor Newton watercolor brushes, Ippolito soon abandoned them and began to paint with twigs and sponges he picked up along the seashore. Finding poetic inspiration in colored tissue, maps, and hand-quilled pages from an accountant's ledger, Ippolito pasted these modest materials into disarmingly insubstantial compositions, sometimes altering the surface with watercolor. The loose handling of material and brush in these Aegean collages gives them a freshness that belies their precious scale and decorative materials.

Although he had brought along an expensive set of the finest Windsor Newton watercolor brushes, Ippolito soon abandoned them and began to paint with twigs and sponges he picked up along the seashore. Finding poetic inspiration in colored tissue, maps, and hand-quilled pages from an accountant's ledger, Ippolito pasted these modest materials into disarmingly insubstantial compositions, sometimes altering the surface with watercolor. The loose handling of material and brush in these Aegean collages gives them a freshness that belies their precious scale and decorative materials.

Upon his return to upstate New York, Ippolito embarked on a new series of oils that integrated the limpid color of his Aegean collages into his by now familiar atmospheric painterliness. Titles such as Aegean Night (1989-90) and Kusadasi Bazaar (1991) signal the lingering influence of the artist's summer by the sea; even such 1992 canvases as Sundance and Southwest Landscape, while ostensibly inspired by a trip to the Arcosanti artist community in Arizona, nevertheless reveal in their vacant compositions and lucid color a debt to the limpid space and light of the Aegean.

1993-2001

Action and Impulse

Angelo Ippolito was not one to sit still for very long, physically or pictorially. He ended his painting career with a decade of experimentation with a new formats and a new preoccupation: jazzy, all-over compositions.

Angelo Ippolito was not one to sit still for very long, physically or pictorially. He ended his painting career with a decade of experimentation with a new formats and a new preoccupation: jazzy, all-over compositions.

As with his Aegean canvases, inspiration for these improvisatory oils came in small packages--specifically in a series of works created on paper during summer residencies in the Umbrian hilltown of Montecastello di Vibio. Again he turned the meager resources of his provisional studio to his advantage, using a palette knife to produce small abstractions in oil on handmade paper. Ippolito returned to Umbria in subsequent summers, producing a prolific set of paintings on paper that he dubbed The Seasons (1992-95), a modest number of larger works on paper known as the Jazz series (1995), and a set of mid-sized oils on paper called the Umbrian series (ca. 1988). Ippolito produced the Siena series, consisting of 85 works on paper, in a burst of creative output during his final visit to Umbria during the summer of 2001.

As with his Aegean canvases, inspiration for these improvisatory oils came in small packages--specifically in a series of works created on paper during summer residencies in the Umbrian hilltown of Montecastello di Vibio. Again he turned the meager resources of his provisional studio to his advantage, using a palette knife to produce small abstractions in oil on handmade paper. Ippolito returned to Umbria in subsequent summers, producing a prolific set of paintings on paper that he dubbed The Seasons (1992-95), a modest number of larger works on paper known as the Jazz series (1995), and a set of mid-sized oils on paper called the Umbrian series (ca. 1988). Ippolito produced the Siena series, consisting of 85 works on paper, in a burst of creative output during his final visit to Umbria during the summer of 2001.

If these works on paper employed a more earthy palette than the Aegean series--replacing the latter's eggshell hues with deep reds, ochres, and violets--the new series of oil paintings that Ippolito produced during winters in his capacious Vestal studio pushed that palette still further, into jarring or discordant color combinations. At the same time Ippolito upped the ante on his compositional gambits, layering stroke after stroke of contrasting colors in a flurry of painterly activity, deliberately choosing oversized brushes to prevent him from being too finicky with any individual mark.

This impulsive, almost stochastic working method--often inspired by listening to Dixieland and Beebop--produced compositional challenges beyond those Ippolito had ever set for himself in the past. The ambition the artist set for each canvas was to resolve a blizzard of brushstrokes spread across different depths of field into a coherent space--even though each brushstroke has little direct relation to its immediate neighbors.

This impulsive, almost stochastic working method--often inspired by listening to Dixieland and Beebop--produced compositional challenges beyond those Ippolito had ever set for himself in the past. The ambition the artist set for each canvas was to resolve a blizzard of brushstrokes spread across different depths of field into a coherent space--even though each brushstroke has little direct relation to its immediate neighbors.

The results of this pictorial gambit are unlike any of the artist's previous compositions; when they succeed, these off-kilter, vertiginous hailstorms of disconnected marks somehow, when stared at long enough, pull together into a dynamic equilibrium. Whether marked by aggressive, contrasting colors or quirky pastel hues, these canvases shouldn't work. Yet like the proverbial perpetual motion machine, they deftly juggle contradictory movements into a sustained choreography. In this sense, they are fitting capstones for an artist whose instincts led him on a circuitous, but ultimately uniquely rewarding, journey through life and art.

News

Follow us on Instagram

Ippolito work to appear in Your Friends & Neighbors

A spirited painting of Ippolito's will appear in season 2 of the hit Apple TV series, which stars John Hamm as a former money manager who now robs his neighbor's homes.

AKG Museum to acquire two historical paintings

The storied AKG Museum (formerly Albright-Knox Gallery) in Buffalo has acquired two large canvases to hang alongside its impressive collection of Abstract Expressionists.

Lawrence Fine Art features Ippolito collage

A 1985 collage appeared in an exhibition about how artists use collage to achieve their visions in fall of 2024.

Springfield Art Museum exhibition highlights art from diverse sources

An Ippolito Berkeley collage from 1961 work is one of the works presented in an group show up till October 2021.

Ippolito work featured in Art Review City

The painting Blue Horizon Line is featured in a 2021 article on Lawrence Fine Arts director Howard Shapiro, whose business has thrived despite the pandemic.

Now represented by Lawrence Fine Arts

As of 2020, the estate of Angelo Ippolito is now represented by Lawrence Fine Arts in East Hampton, New York, one of the preeminent galleries for midcentury artists.

Lois Dodd to speak on Ippolito's work

Renowned artist Lois Dodd will speak on the 10th Street scene at Ippolito's Yvette Torres Fine Art exhibition on Sunday 5 August 2018 at 4pm.

Rockland opening announced

Rockland's First Friday art walk on 3 August 2018 will be the occasion for the opening of a summer exhibition of large paintings and smaller works on paper at Yvette Torres Fine Art.

New website launched

This comprehensive website surveying all the major series of works by Angelo Ippolito was launched in 2018. More information will be added in the coming years--especially on the historical role the artist played in the midcentury New York art world.

Cynthia Hart Durfey interviewed on Angelo's work

Springfield Art Museum director Ann Fortescue interviewed artist Cynthia Hart Durfey on her experience as a fellow artist and companion of Angelo Ippolito's in the 10th Street art scene on 2 April 2018. A video is forthcoming.

Yvette Torres plans major exhibition

A full-gallery show of Ippolito's paintings and works on paper is being organized for August 2018 by Yvette Torres Fine Art, a venerable gallery in Rockland, Maine's lively art capital, whose shows have been described as "museum worthy."

NYU show examines Ippolito's historic role

The groundbreaking exhibition "Inventing Downtown" celebrates the transformation of the New York art scene by artist-run galleries, beginning with the Tanager Gallery co-founded by Angelo Ippolito and Fred Mitchell in 1952.

Dayton Art Institute acquires October II

The colorful 1982 canvas is now in the collection of the Dayton Art Institute, where it joins works by Ippolito's compatriots such as Willem DeKooning, Mark Rothko, and Fairfield Porter.

Praise for Springfield retrospective

The Springfield Museum exhibition makes the cover story of the 2011 Gallery Guide, while press calls it "a joy" (Columbus Dispatch) and Ippolito "an artist's artist" (Springfield News-Sun).

Intimate abstractions in Belfast, Maine

Between Sky and Sea, a solo exhibition of smaller works, opens August 13th, 2010 at the Beaver Street gallery.

2011 retrospective in Springfield

A major Ippolito exhibition is planned for the Springfield Museum of Art, to open in January 2011.

Two gems enter Colby collection

The Colby Museum of Art has acquired Bridge and Spring Rain, two lively paintings from the 1980s.

Yale acquires important early work

Renowned collector Richard Brown Baker has donated Angelo Ippolito's 1955 painting Midday to the Yale University Art Gallery. An early supporter of Ippolito's work, Baker wrote a heartfelt appraisal that is printed in the 2008 Yale Bulletin.

Solo exhibition at UMMA

The University of Maine Museum of Art in Bangor mounted a show of large abstractions, including several from the Regatta series, from October 2008 to January 2009.

Summer and fall exhibitions

Ippolito's painting September appeared in the exhibition Summer Set 2008 at David Findlay Jr. from 5 July to 23 August, while a major solo exhibition at the University of Maine Museum of Art is planned for October.

Art of the Gesture at David Findlay Jr

Ippolito's work is featured in this catalogue and exhibition at 41 E. 57th Street in New York from April 5 to 26, 2008. The opening reception is Saturday, April 5, 3:00-5:00pm.

Springfield Museum acquires three works

The Springfield Museum of Art acquired three Ippolito paintings from the 1960s and 1990s and exhibited them in the exhibition Primo! in February 2008.

Bangor celebrates Ippolito acquisition

Kristen Andresen of the Bangor Daily News applauds the "bold, colorful" works by this "pivotal" artist, while UMMA calls the acquisition a "significant boost" to the university.

UMaine museum acquires major paintings

University President Robert Kennedy announced a major acquisition by the recently expanded museum in downtown Bangor in a special event on December 6, 2007. Read the press release or watch a video of the announcement.

Abstract Impulse exhibition in fall 2007

Ippolito's painting Roundabout, recently acquired by the National Academy in New York City, will be featured in this exhibition. The show runs from 1 August 2007 to 6 January 2008 with a reception on 18 September, and includes a catalogue by Academy curator Marshall Price.

Ippolito in Smithsonian publication

A story about Ippolito's younger days by Cynthia Hart appears in A Thousand Kisses: Love Letters from the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art, to be published by HarperCollins in 2007.

Summer 2007 show at David Findlay Jr

Ippolito's Evening Landscape is featured in the summer exhibition at David Findlay Jr. Fine Art in New York.

Kane film reviews Tanager history

Richard Kane has produced a new film on painter Lois Dodd, one of the original members of the historic Tanager gallery co-founded by Angelo Ippolito. The film includes vintage photographs of Ippolito from the early 10th Street days of the New York School; it premieres in Rockland, Maine in August 2007 and in New York City the following November.

Ippolito inducted into National Academy

Angelo Ippolito has been formally inducted into the National Academy of Design, joining the company of many of the most distinguished artists of our time. The National Academy is located at 1083 Fifth Avenue in New York City. The induction was recently announced but Angelo was formally approved as early as April 18, 2001.

Portrait featured in Alexandre Gallery

A portrait of Angelo by sculptor William ["Bill"] King is featured in "The Early Work of William King" from December 2 through January 27 at the Alexandre Gallery on 57th Street in New York. This famous bust also appears in the show's catalogue.

Sept 2006 solo show at David Findlay Jr, NYC

A solo show of Ippolito's Regatta Series kicks off the fall season at New York's David Findlay Jr. Fine Art Saturday September 9th from 3-5pm. Curated by Louis Newman and Dallas Dunn, the exhibition features over a dozen major oils from this little-known series by the artist and runs from 2-27 September 2006.

Regatta panoramas acquired by Roberson Center

Three of the largest works in the Regatta Series were acquired in the past year by the Roberson Museum and Science Center in Binghamton, New York. The recently renovated museum is well suited to displaying these panoramic works, over nine feet in length each.